Sergio Leone’s iconic Spaghetti Western The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly has a more complex meaning beyond its surface title. Widely considered to be the definitive Western movie, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly was released in 1966. This was a low point in Hollywood when Americans, according to critic Christopher Frayling, were “bored with an exhausted Hollywood genre.” (Archive.org) Something had to bring back those exhausted audiences – and Leone was the filmmaker for the job, creating a grandiose, gunslinging masterpiece that’s as much a satire of the genre as it’s indulgent in its conventions.

The 1960s were also a time of polarization and opposition regarding the war in Vietnam, with many Americans appalled by its devastation. The Civil War backdrop of The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly, filmed in Spain, sets the scene for three gunslingers relentlessly competing for buried Confederate gold. It paints a picture of an unforgiving wasteland rather than the exotic land of promise of previous decades. On the surface, Leone presents three archetypal characters. The straightforwardness of those archetypes is thrown into question. Through the movie’s double-crossing twists and turns, he shows it’s not that simple anymore, and never will be again.

The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly’s Title Refers To The 3 Main Characters

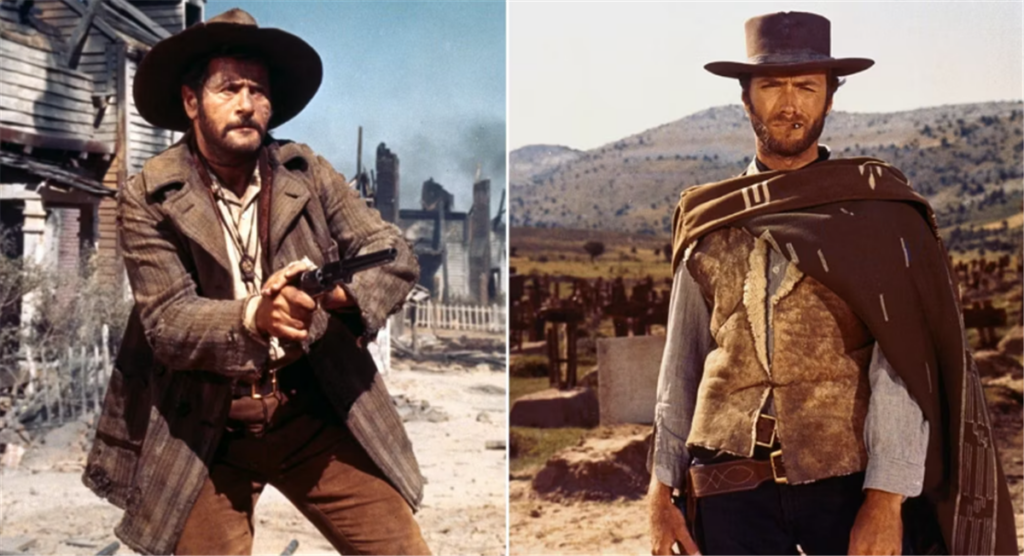

The title serves as a shorthand for the main characters. Clint Eastwood’s iconic character Blondie – ‘The Good’ – hunts for outlaws, but his ultimate goal is the hidden cache. Eli Wallach’s portrayal of Tuco — ‘The Ugly’ – is a ruthless bandit with a distinctive grimace and a propensity for profanity. He holds the key to the location of the hidden gold but only knows the cemetery where it’s buried. Lee Van Cleef embodies a cold-blooded killer, Angel Eyes – ‘The Bad’. Driven solely by a thirst for gold, Angel Eyes is the most ruthless of the three, and the true villain of the story.

These iconic introductions, paired with their morally suggestive titles, have become a touchstone for Westerns and beyond.

Each gunslinger bursts onto the scene in a way that cements their title. Clint Eastwood’s The Man With No Name emerges heroically from a dusty haze, immediately distinguishing as a fearsome loner. Tuco’s grand entrance involves a desperate leap, showcasing his impulsiveness and micheivous tendencies. Angel Eyes, meanwhile, is shrouded in silent mystery, his gaze providing a clear hint of his sinister nature. These iconic introductions, paired with their morally suggestive titles, have become a touchstone for Westerns and beyond, most notably used by Quentin Tarantino in Kill Bill: Vol 1 for dramatic flair.

The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly’s Title Has Another Interpretation

All three title qualities apply to each of the men to some degree – even if it’s only a surface expectation. Tuco’s “ugly” traits are put on display early on – criminality, crassness, and buffoonery. Tuco blossoms throughout, a complex mixture of tenderness and cruelty. Some kindnesses, like offering a sun-blistered Blondie water and coffee, are motivated by using him. Other times, he shows genuine camaraderie with Blondie. One of the best quotes from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is attributed to Tuco in a scene that highlights his moral hypocrisy, with him accusing his priest brother of simply being “too cowardly” to be a bandit like him.

Advertisement

Angel Eyes has considerably less redeemable qualities, given that the character is clearly shown to be a merciless killer. However, his portrayal is not without nuance. As The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, explains, Angel Eyes does have some sense of honor. He won’t take money for a job without making sure he sees it through to the end.

Eastwood’s heroes are more antiheroic than the idealized American values of John Wayne.

Similarly, Blondie is also not straightforwardly good. Eastwood plays some of the best Western protagonists, his heroes more antiheroic than the idealized American values of John Wayne. His dry humor is part of what gives him this antiheroic appeal – when Tuco comments on the peace of the graveyard, Blondie replies, “Like a cemetery for instance?” with brilliant deadpan. He maintains a degree of mystery at every turn, especially using Tuco’s noose trick against him at the end. Ironically, though, concluding with shooting the rope and bringing the story full circle, polarity is restored – Blondie is ultimately good, Tuco has been taught a lesson, and Angel Eyes, the undisputed baddie, is defeated.

How The Good, The Bad And The Ugly Became Part Of The English Lexicon

The phrase entering the English language has its roots in the film’s production. Screenwriter Luciano Vincenzoni thought of the Italian title “Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo” – “The Good, the Ugly, the Bad.” This title was used for the Italian release. However, for English-speaking audiences in the US and UK, the title was changed to “The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly.” This alteration improved the rhythm and flow of the title for English speakers. Beyond the film, the phrase has taken on a life of its own, used to describe a well-rounded view of any topic.

Its ubiquity in language was helped along by Robert F. Kennedy’s use in his speeches.

For instance, people can talk about “the good, the bad, and the ugly” of being a Manchester United fan, with all its ups and downs. American politician Robert F. Kennedy even made frequent use of the title in his public speeches. But ultimately, its importance to pop culture is hardly surprising; after all, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly has a well-earned reputation as one of the greatest Westerns ever made.